One Family Photo:

Leader in Me #6

Synergize

Calvin's school uses the Leader in Me curriculum, which is The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People adapted for kids.

Leader in Me #6: SYNERGIZE

In habit 6, Stephen Covey defines synergy as creative cooperation where valuing differences leads to a whole greater than the sum of its parts. Then he describes peak synergy as a time his corporate leaders went on a nature retreat to draft their corporate mission statement.

The resulting corporate mission statement reads: Our mission is to empower people and organizations to significantly increase their performance capabilities in order to achieve worthwhile purposes through understanding and living principle-centered leadership.

That mission statement, and the word synergy itself, is a hodgepodge of corporate-speak that makes me want to barf.

It's funny, because my company believes in synergy. I believe in synergy. It's why we chose to work together as a cooperative instead of a nebulous collection of parallel independent consultants. We even spent some of our face-to-face time this year refining a manifesto of sorts. But if I suggested in our group chat that we take a weekend to synergize on our corporate mission statement, I know which custom emojis my coworkers would send in response. I'd send them too.

Maybe our revulsion it's because corporate-speak is easy. It's easy for corporate leaders to talk about synergy and "significantly increasing performance capabilities". Real ones do it. Doing it is hard. So hard, in my experience real leaders don't waste time talking about synergy because you're too busy modeling it.

--

Speaking of models, Harry Markowitz, the Nobel Prize-winning economist who developed Modern Portfolio Theory, famously called diversification, "the closest thing to a free lunch in investing," which seems to align with valuing differences and synergy.

If that's not nerdy enough for you, I've been thinking about synergy through the lens of vector analysis:

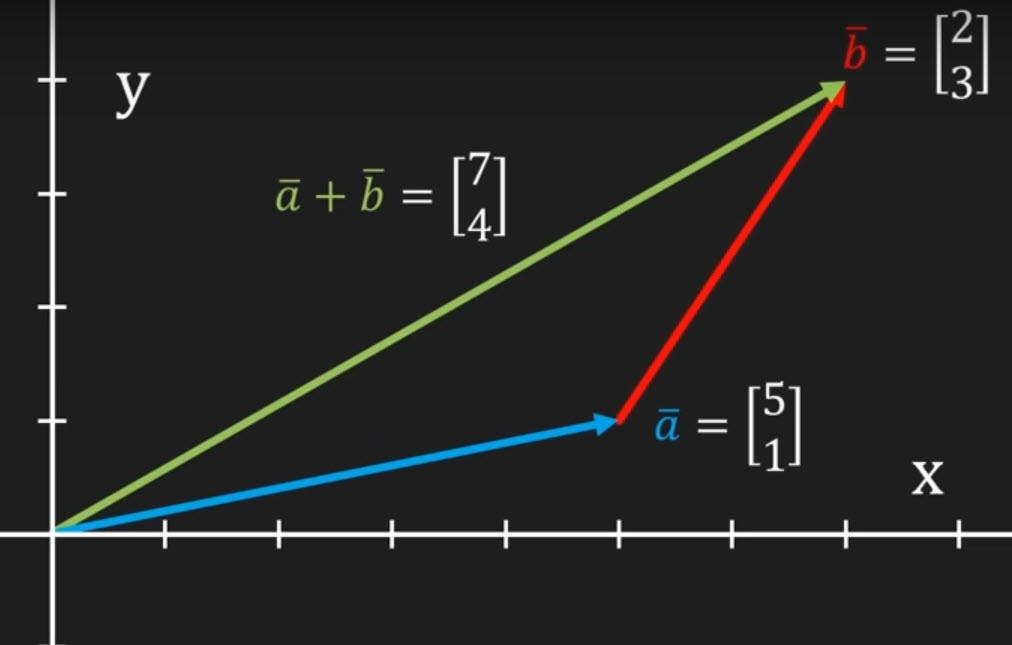

You can add two vectors together by stacking the beginning of the first one to the end of the second one. When two vectors point in the same direction, their sum has the maximum possible magnitude. But another important attribute of two vectors is their cross product, which relates to torque and stability. A cross product's magnitude corresponds to the area of the parallelogram formed by the two vectors. If two vectors point in exactly the same direction, their cross product is zero, meaning they have no torque or rotational stability. People's abilities and experiences are sort of like vectors—diversity leads to real-world stability.

--

Luana and I are very different. We have different strengths and experiences. There are things I am quite bad at that she is naturally, effortlessly amazing at. I'm thankful for those differences. I'm grateful for our creative cooperation as we grow our family together.

One Dad Joke:

A Team Effort

*Credit: @bekindofwitty

Highlights:

Cooperation

All Together Now by Morgan Housel

A few years ago a group of researchers ran a massive experiment on Facebook. By tweaking users’ newsfeeds – controlling what people saw – they could influence what kind of posts those users would generate themselves. “When positive expressions were reduced, people produced fewer positive posts and more negative posts; when negative expressions were reduced, the opposite pattern occurred.”

When this happens – there’s a whole field of study about this process, called emotional contagion – people never say, “Oh, I acted this way because I was influenced by everyone else around me.” Everyone assumes they come up with their own decisions independently, in their own head.

Years ago I interviewed Yale economist Robert Shiller. He said something that stuck with me: “You have to realize, your thoughts are not really your own thoughts. They percolate in from other places and from other people.”

... One takeaway here is that when you realize how susceptible you are to others’ emotions, you become more thoughtful about who you surround yourself with. Who you follow on Twitter, who you watch on TV, where you work, who you hang out with after work. Who you marry – that’s a huge one. The higher the stakes, the more thoughtful you need to be about those who surround you.

But emotions will always be contagious. Bill Seidman, the former head of the FDIC, once said, “You never know what the American public is going to do, but you know that they will do it all at once.”

This essay is about how we made our first home together. By home I don’t mean just the physical structure, but the emotional space in which the coevolutionary loop plays out. ... Having diverging goals was the sort of thing that had, in previous relationships of mine, been a source of conflict. But with Johanna, there was rarely such friction. It was more like our conflicting needs were two equations, and our task was to figure out where they intersected; the hardness of the problem wasn’t personal. ... But was there a solution?

It was hard to tell, but this wasn’t necessarily a disadvantage. The hardness of the problem might even be a good thing, I figured: it would force us to be more creative. When you write classical poetry, as I liked to do, you impose strict rules on yourself to deliberately make it harder to say what you want—and this is what makes poetry come alive. W.H. Auden, the British poet, praised metrical rules because they “forbid automatic responses, force us to have second thoughts, free from the fetters of Self.” The same thing is true for relationships, I reasoned: I could chart a path through life that made no compromises for others, and it would go where I wanted it to; or I could impose the much stricter rigor that comes from aligning my trajectory with Johanna’s, seeking mutual flourishing, and I’d be surprised where life would take me. ... It took us two months to go from talking about moving in together to signing the papers on the house. On the train back from the visit to my grandparents, I was on the phone with my father, discussing how to draw up the contract.

And then the loop went on: living in the new situations we created, we got access to new experiences which we rapidly brought to the surface. We kept on iterating. Changing our environment and our relationship, learning, and changing things again. ... —Sundays are for listing everything that went wrong during the week on the blackboard we painted on the wall of my study, so we can figure out what needs to change.

This latter habit was the most important. I was learning to program, and so I liked to think about our life as a piece of software. We had our routines and our principles, this was the code. We ran the code by living it. The list on the blackboard was the bug log, a record of the ways our routines broke down in contact with reality. We kept going through the code until our life did what we wanted it to do, more or less. ... The bug log was, I realize now, a way of making the coevolutionary loop explicit. Writing down everything that went wrong helped us pinpoint the bottlenecks, the frictions. It also forced us to put words to our goals, values, and assumptions, opening those up for discussion and refinement. Is that really what you want? What are you willing to give up to achieve it? How do you feel about it?

This, day after day, was how we grew a home.

iamJoshKnox Highlight:

I'm working on a music project.

More on this later, but please reply if you'd be interested in lending some of your time and musical taste.

Want to Chat?

Schedule some time on my calendar:

Book some time even if you don't know what you want to talk about: https://calendly.com/iamjoshknox

Until next week, iamJoshKnox