#174 - Classes

1 Family Photo, 1 Dad-Joke, Many Highlights

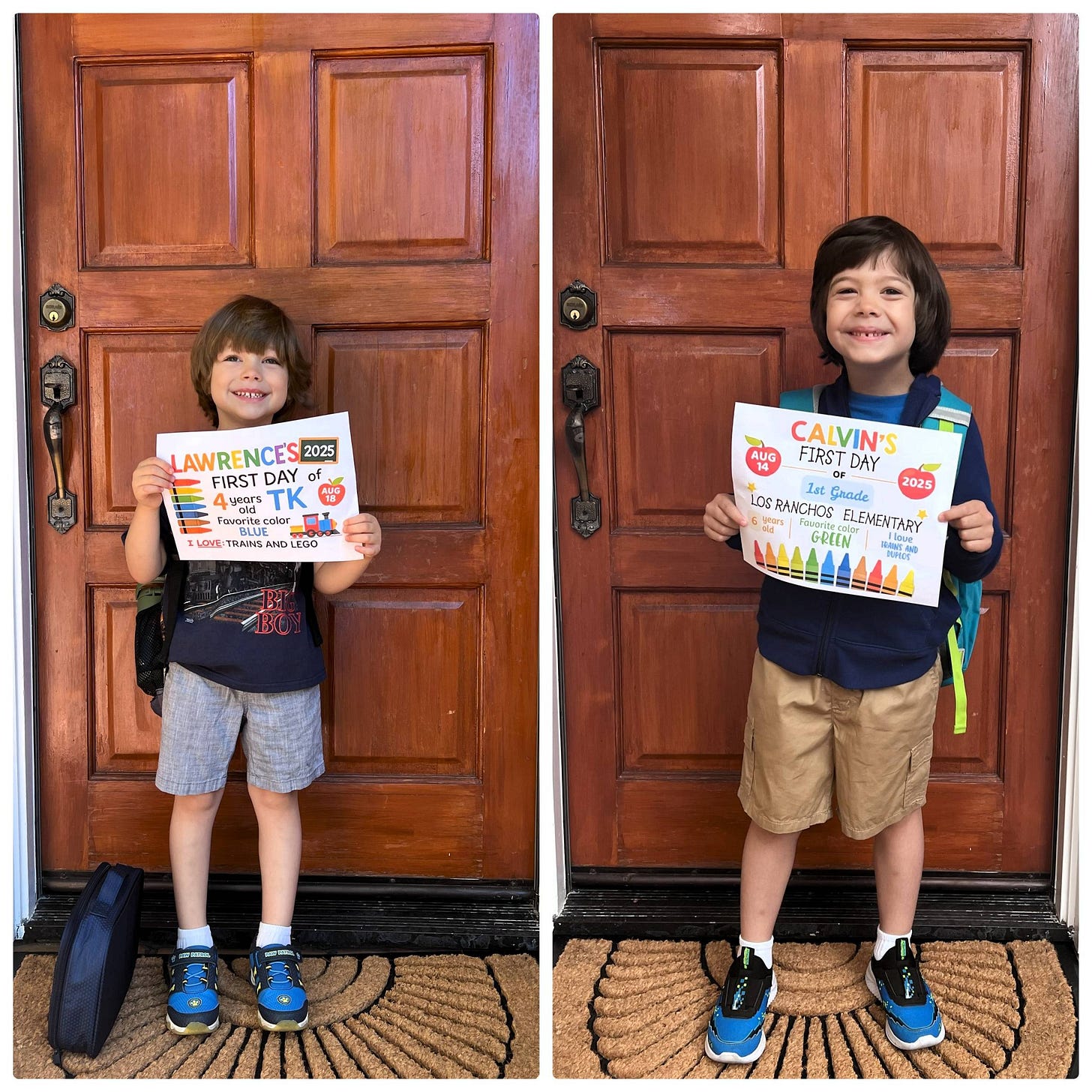

Family Photo: Classes

Calvin and Lawrence both started school this week. Hooray!

--

Before classes started, the principal sent a mass email to all the schoolparents, politely asking them not to freak out over class assignments (emphasis mine):

I know there is excitement mixed with apprehension on your end about which teacher your child will have, and which students will be in class with your child. I want to let you know that teachers, staff, and I put an incredible amount of thought and energy into creating class rosters. There are multiple factors that teachers take into account when placing students into the next grade level. I encourage you to build positivity with your child about their newly assigned classroom and teacher! No matter what name you see this afternoon, smile big, and tell your child how awesome this school year is going to be! YOU are massively influential in setting the tone for the year.

That got me thinking. What is the correct way to create class rosters?

Imagine there are three 1st grade teachers and sixty 1st graders: what’s the best way to group the 1st graders into three classes of 20 students?

Thought 1: Let Data Decide

What if you could perfectly sort the sixty students on some dimension? You could put the top third in one class, the bottom third in another, and the middle third in the final class. This would minimize variance within each class. Teachers could focus their instruction to a specific level within their grade. Within each class, the top students would be less likely to get bored, the bottom students would be less likely get overwhelmed.

What would be the right dimension? Ability? Potential? Test performance?

Do you pair the best teacher with the A-students so they can go the farthest? Or with the C-students so they can catch up?

Would that be equitable? Would it even be legal?

Also, these kids have to grow up and live in *society*. A sorted grouping might be best for academic-learning, but it can’t be best for life-learning to only surround students with the kids most like themselves. For that, maybe each class should be an even mix of students across the distribution? High-ranked students could help low-ranked students improve, a highly-transferrable skill in professional life.

Thought 2: Let Teachers Decide

But students are multi-dimensional. Many student attributes affect class composition: intellect, kindness, politeness, confidence, attentiveness. We are not very good at ranking most of these.

Maybe teachers can intuit all these dimensions into a comprehensive score.

In my head, I imagine the 1st grade teachers getting together over chips and beer to draft their classes like a fantasy football team. Do they use a snake order draft? Is 1st pick randomly selected or determined by seniority? Are they allowed to trade picks?

This doesn’t seem legal either, but I’d love to be in the teacher-draft groupchat.

Thought 3: Let Markets Decide

The economist in me thinks, “What if you created classes based on willingness to pay?”

You could auction off teacher/class assignments to the parents most concerned about this sort of thing. Would it be fair to let the parents who paid the most put their kids in preferred classes? What if those excess funds were used to improve the other classes?

Again, this doesn’t seem like it would be legal. I’ve never tried walking into the front office with a bribe...it seems like it would be frowned upon at the very least.

Though isn’t this the basic arrangement we have with private schools and funding public schools with tax dollars?

Thought 4: Avoid Disruption

I asked a teacher-friend of mine about class creation. He said I was overthinking it.

The main feature of class construction is just making sure the most disruptive students are evenly distributed between the classes. Imagine there are three really disruptive students, you want each one isolated in a separate class instead of all three together where they can ping-pong off each other and create contagion.

That’s fair.

The principal ended his email:

We have selected incredible teachers to work with your children this year. And It’s going to be a great!

I believe him.

Our school is one of 12 Blue Ribbon elementary schools in the state of California. All three 1st grade teachers seem qualified and capable. It’s a desirable place to work.

The parents here are highly engaged. I opened an email about volunteering in the classroom, an hour after it was sent, and the dozen volunteer spots were already signed-up.

The biggest influence on the population of students (and parents) at our school is where we live. The distribution within that population probably doesn’t matter as much.

I’m sure Calvin and Lawrence have great classes.

It’s also reassuring to know the principal’s own 1st grade daughter attends our school. She’s in Calvin’s class.

Dad Jokes:

Classified

Source: The Onion

Highlights:

Class Cultures

Walking South LA by Chris Arnade

South LA is a modern version of the 50s, the one Hollywood once churned out many glamorized and romantized versions of. A humble town with an extensive lower middle class focused on hard gritty work and dedicated to family, faith, and the flag.

The only wrinkle being everyone now is a lot less white than in that older version. Most are second or third generation immigrants, either from Mexico, Central America, Vietnam, or China.

It’s a real world version of the American Dream that should be celebrated by both political parties. The left for its diversity and working class roots, the right for its industry, faith, and family values.

Culture Studies by Henrik Karlsson

I spent more hours studying Spanish in school than I spent on English, but testing myself right now, I can’t count beyond treinta y nueve, 39. Spanish wasn’t valued in my peer culture in rural Sweden the same way as English — the language of Hollywood, video games, and internet forums. Compared with all that, 520 classroom hours won’t get you far.

If the culture in a school is at odds with its pedagogical goals, energy will be wasted trying to deal with the friction between these value systems: You get disruptive students and motivation issues. An educator might have an easier time if they found a way to align the peer culture with the pedagogy. But crafting aligned cultures is not how mainstream education works. Rather, culture is treated largely as a constant — natural, if sometimes frustrating, and beyond the scope of educators. Schools do not shape culture; they find strategies to work with the cultures they stumble into. When chaos descended on my Spanish classes, my teachers responded by locking the most disruptive boys in a room in the back, trying new pedagogical tactics — group assignments, role play, watching Spanish films — and increasing the amount of time we studied. But the culture remained.

...Culture is a catalyst. It multiplies the effectiveness of all other interventions and tools. A kid that grows up in an academically oriented family might use the internet to accelerate their rate of learning. The same kid in a different context might use the same tool to distract herself. Knowing how to scale up cultures that support us would be immensely useful, but it is a difficult problem.

Most educational movements have not focused seriously on solving it. But there are some exceptions, movements that have gone beyond curriculum and pedagogy and designed their schools explicitly to promote the formation of certain cultures. Two examples that stand out to me are Jesuit and Montessori schools. Both have (or had) distinct cultures that differ markedly from the norm and actively work to maintain and scale them up. The particular cultures they promote are in many ways opposites — traditional Jesuit schools were conservative and gave teachers great authority, while Montessori schools are progressive and child-centered — and I’m not sure the specifics of either are ideal for most children. But I think we might learn something by looking at how they grew.

...The [Jesuit] colleges were strictly hierarchical, in a rank order codified by Loyola: God at the top, below him the priests, then the seminary students, and finally, the lay students. Inside of each category, there were finer hierarchical gradations. The standard Jesuit response to large class sizes was to divide students into groups of 10 called decuries, which would be led by a top student called a decurion who would assist the instructor with grading, supervising, and even discipline.3

Loyola, a soldier who fought in many battles before undergoing a spiritual conversion at 30 after a grave injury at the Battle of Pamplona, modeled the colleges partly on the military. Students were expected to submit to their superiors. In the classrooms, pupils sat in rows arranged not by age but by how far along they were in their studies. Rows would take turns reciting Latin, conjugating, paraphrasing, and so on. The students seated closest to the teacher would be given the most difficult assignments. As they improved, they would progress row by row, getting closer to the teacher until they were promoted to the next class.

...Maria Montessori’s vision of childhood was greatly at odds with the Jesuit ideal of strict hierarchy and discipline. She believed that children should have great freedom to choose what to work on and limited structure for how to approach it...

...In both Montessori schools and Jesuit colleges, instructors deliberately manipulate their students’ social hierarchy, regulating how much influence various members have over the group. If the students who command respect embody the values the institution is trying to instill, those values will be amplified through social imitation. If, on the other hand, people who command respect are those trying to subvert the values of the institution, the culture will work against the skills, norms, and behaviors the institution is trying to instill.

...If you tried to impose the same type of consistent culture in government schools, there would be intense pushback. And for good reason: Public schools accommodate a much wider set of stakeholders, none of whom can impose their vision on the others. Public schools are legally committed to basic liberal ethics, including not infringing on students’ personal beliefs. This is a powerful ideal. But it can leave them with a muddle of a culture, which makes it harder to achieve the kind of focus and alignment required in an effective learning institution.

When families deliberately choose educational alternatives, on the other hand, there is room for a more radical and far-reaching alignment between the participants. Montessori organizations put out pamphlets detailing a vision of education and encourage parents to compare self-proclaimed Montessori schools with their standards. This puts pressure on schools that use the name but diverge culturally. In this way, the shared vision pushes the instructors and families to align (or break off to form new lineages). By making the values clear and having people opt in, there is less friction to overcome, less work necessary in making sure that the participants share in the culture.

The Jesuit colleges and Montessori schools see themselves as more than just schools. They see themselves as instruments that work to bring about a new world — starting with children. They have very specific and divergent ideas about how that world should look, what kinds of virtues will help create it, and how children are to be raised to achieve those aims. But they share the insistence on a large value system. And they have converged on a set of practices — age-mixing, status manipulation, lineage traditions, and opt-in membership — in an attempt to deal with the problem of how to scale up their cultures without losing what makes them unique.

How the Ivy League Broke America by David Brooks

Over time, America developed two entirely different approaches to parenting. Working-class parents still practice what the sociologist Annette Lareau, in her book Unequal Childhoods, called “natural growth” parenting. They let kids be kids, allowing them to wander and explore. College-educated parents, in contrast, practice “concerted cultivation,” ferrying their kids from one supervised skill-building, résumé-enhancing activity to another. It turns out that if you put parents in a highly competitive status race, they will go completely bonkers trying to hone their kids into little avatars of success.

...And yet it’s not obvious that we have produced either a better leadership class or a healthier relationship between our society and its elites. Generations of young geniuses were given the most lavish education in the history of the world, and then decided to take their talents to finance and consulting. For instance, Princeton’s unofficial motto is “In the nation’s service and the service of humanity”—and yet every year, about a fifth of its graduating class decides to serve humanity by going into banking or consulting or some other well-remunerated finance job.

Everything I Know About Elite America I Learned From ‘Fresh Prince’ and ‘West Wing’ by Rob Henderson

It’s possible I watched more TV from birth to age 17 than most upper-class Americans watch their entire lives.

...Along the way, I’ve learned about the complicated ways that class interacts with taste, and what different social classes view as desirable. What I’ve come to realize, as I reflect on different influences in my life, is that the television I’ve watched has made me a different person than I would otherwise have been; choices I’ve made have been guided to a large degree by what TV has taught me about what constitutes a good life.

...In the O.C. — what a friend called “‘Fresh Prince’ with white people” — Ryan, a teenager from a rough neighborhood, moves in with a rich family, the Cohens. At first, he is seen as a troublemaker, but we soon find out he’s a talented student (though he, too, feels out of place at his new private high school).

...Television, in other words, gave me an aspirational road map for upward mobility.

iamJoshKnox Highlights:

AI Creativity Workshop

Want to learn more about thoughtful, creative uses of AI? Want to visit San Luis Obispo?

In September, I’m doing an AI Creativity Workshop program with the Lifelong Learners of the Central Coast.

Want to Chat?

Book some time even if you don’t know what you want to talk about:

https://calendly.com/iamjoshknox

Until next week,

iamJoshKnox

Thanks for writing this, it clarifies a lot. Data sorting, so clever!